home // store // text

files

// multimedia // discography // a

to zed

// random

// links home // store // text

files

// multimedia // discography // a

to zed

// random

// links

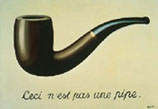

Perhaps

the mock documentary owes its existence to a single Belgian painter

who startled the art world in 1929 with La Trahison des Images.

This is, of course, René Magritte's famed oil painting

of a pipe, beneath which are painted in pretty cursive the words,

"Ceci n'est pas une pipe" — "this is not

a pipe." Perhaps

the mock documentary owes its existence to a single Belgian painter

who startled the art world in 1929 with La Trahison des Images.

This is, of course, René Magritte's famed oil painting

of a pipe, beneath which are painted in pretty cursive the words,

"Ceci n'est pas une pipe" — "this is not

a pipe."

The painting is a challenge,

not just to anyone who sees it but to the artistic establishment

as a whole. Magritte presents the viewer with a choice: Do you

believe your eyes, or do you believe what I'm telling you to

believe? By placing the object and its written description in

diametrical opposition, Magritte deliberately leaves the viewer

in artistic limbo. A successful mock documentary can have the

same effect on a viewer, leaving her to wonder, "Could that

actually have happened?" or, perhaps even, "Was that

for real?" The answer to the latter question, depending

on how one looks at it, is either Yes or No: Yes, that was a

real film you just saw; No, that was not an actual occurrence

depicted within it. Like Magritte's painting, there is no sure

answer. Is it a pipe? Or is it not a pipe? The painting is a challenge,

not just to anyone who sees it but to the artistic establishment

as a whole. Magritte presents the viewer with a choice: Do you

believe your eyes, or do you believe what I'm telling you to

believe? By placing the object and its written description in

diametrical opposition, Magritte deliberately leaves the viewer

in artistic limbo. A successful mock documentary can have the

same effect on a viewer, leaving her to wonder, "Could that

actually have happened?" or, perhaps even, "Was that

for real?" The answer to the latter question, depending

on how one looks at it, is either Yes or No: Yes, that was a

real film you just saw; No, that was not an actual occurrence

depicted within it. Like Magritte's painting, there is no sure

answer. Is it a pipe? Or is it not a pipe?

Of course, one one level,

Magritte is being totally honest with the viewers of his painting.

What they are seeing is not a pipe per se, but a representation

of a pipe. So, no, it's not a pipe. It's a painting of a pipe.

That hidden degree of honesty that Magritte proffers to the viewer

is not unlike the hidden kernel of truth, exhibited as a grounding

in the actual world, that is present in most mock documentaries. Of course, one one level,

Magritte is being totally honest with the viewers of his painting.

What they are seeing is not a pipe per se, but a representation

of a pipe. So, no, it's not a pipe. It's a painting of a pipe.

That hidden degree of honesty that Magritte proffers to the viewer

is not unlike the hidden kernel of truth, exhibited as a grounding

in the actual world, that is present in most mock documentaries.

Though, obviously, a painting

is not a movie and a movie is not a painting, La Trahison des

Images is an important predecessor to mock documentary. The pipe

in Magritte's painting cannot conceivably be of anything but

a pipe, just as the mediocre heavy metal band in This Is Spinal

Tap (1984) cannot conceivably be anything other than a mediocre

heavy metal band. The meaning of each of the pieces, however,

lies in the interplay between what one sees and how one sees

it. The title of the painting—"The Treachery of Images"—succinctly

applies to the operating principle of the mock documentary, as

well. Such films do not simply project an alternate "world"

for their spectators to observe—that is the domain of traditional

narrative cinema, to which the mock documentary obviously owes

a great deal. Mock documentaries use the language of documentary

to subvert the ways in which documentaries are made and viewed.

They take the tools documentary uses to produce "truth"

(or a semblance thereof) and use them instead to produce fictions.

They use familiar conventions to trick us. Though, obviously, a painting

is not a movie and a movie is not a painting, La Trahison des

Images is an important predecessor to mock documentary. The pipe

in Magritte's painting cannot conceivably be of anything but

a pipe, just as the mediocre heavy metal band in This Is Spinal

Tap (1984) cannot conceivably be anything other than a mediocre

heavy metal band. The meaning of each of the pieces, however,

lies in the interplay between what one sees and how one sees

it. The title of the painting—"The Treachery of Images"—succinctly

applies to the operating principle of the mock documentary, as

well. Such films do not simply project an alternate "world"

for their spectators to observe—that is the domain of traditional

narrative cinema, to which the mock documentary obviously owes

a great deal. Mock documentaries use the language of documentary

to subvert the ways in which documentaries are made and viewed.

They take the tools documentary uses to produce "truth"

(or a semblance thereof) and use them instead to produce fictions.

They use familiar conventions to trick us.

Mock documentaries raise several

questions which I will address. How do directors of mock documentaries

render their fictions believable? How do they use the language

of documentary to subvert documentary form? How important is

it that we buy into the film's central conceit; i.e., will the

films "work" even if we do not believe in their authenticity

as documentaries? How do mock documentary films differentiate

themselves from actual documentaries, and how do they tip their

hands to let the viewers in on the joke? Why are most mock documentaries

played for comedy? And is it possible to produce a definition

of the mock documentary? Mock documentaries raise several

questions which I will address. How do directors of mock documentaries

render their fictions believable? How do they use the language

of documentary to subvert documentary form? How important is

it that we buy into the film's central conceit; i.e., will the

films "work" even if we do not believe in their authenticity

as documentaries? How do mock documentary films differentiate

themselves from actual documentaries, and how do they tip their

hands to let the viewers in on the joke? Why are most mock documentaries

played for comedy? And is it possible to produce a definition

of the mock documentary?

read more

>>>>>> |